Nutrient Sensing, Inositol Pyrophosphates and Responses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

The decision to enter stationary phase

Saccharomyces cerevisiae monitors nutrient resources to make decisions on whether or not to keep dividing. We have started to investigate a phosphatase that is important to enable cells to correctly make this decision. We found that wild-type cells (as shown on the left) cycle the purine-cytosine permease - which is responsible for import of nucleobases - from the plasma membrane to the vacuole for destruction. In the phosphatase mutant, the distribution of this protein is different, consistent with the observation that activity of the phosphatase is important for cellular decisions.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae monitors nutrient resources to make decisions on whether or not to keep dividing. We have started to investigate a phosphatase that is important to enable cells to correctly make this decision. We found that wild-type cells (as shown on the left) cycle the purine-cytosine permease - which is responsible for import of nucleobases - from the plasma membrane to the vacuole for destruction. In the phosphatase mutant, the distribution of this protein is different, consistent with the observation that activity of the phosphatase is important for cellular decisions.

Inositol Pyrophosphates

Inositol pyrophosphates are highly charged, multiply-phosphorylated forms of inositol that carry one or more diphospho groups in addition to single (mono) phosphates. These molecules play important and varied roles in eukaryotic cells, affecting energy metabolism, endocytosis and protein trafficking, telomere length and DNA repair, and stress responses. We're interested in understanding the mechanisms that allow inositol pyrophosphates to affect these various cellular functions.

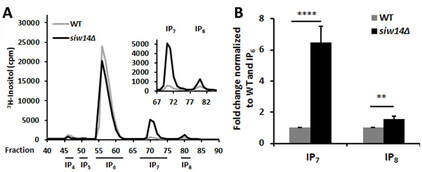

We reported the discovery of a new inositol pyrophosphate phosphatase, specific for the 5-diphosphoinositol pentakisphosphate (aka, 5-IP7), and encoded by the SIW14 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Steidle et al., 2016, J Biol. Chem. 291, 6772-6783). In the absence of this enzyme, inositol pyrophosphates increased by 6.5-fold. This enzyme has an interesting fold and performs a non-standard phosphatase reaction; the structure was published in collaboration with Stephen Shears (Wang et al., 2018, J Biol. Chem 293, 6905-6914) and also by Tyler Florio in Gino Cingolani's group (Florio et al., 2019, Biochemistry 58, 534-545).

Inositol pyrophosphates are highly charged, multiply-phosphorylated forms of inositol that carry one or more diphospho groups in addition to single (mono) phosphates. These molecules play important and varied roles in eukaryotic cells, affecting energy metabolism, endocytosis and protein trafficking, telomere length and DNA repair, and stress responses. We're interested in understanding the mechanisms that allow inositol pyrophosphates to affect these various cellular functions.

We reported the discovery of a new inositol pyrophosphate phosphatase, specific for the 5-diphosphoinositol pentakisphosphate (aka, 5-IP7), and encoded by the SIW14 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Steidle et al., 2016, J Biol. Chem. 291, 6772-6783). In the absence of this enzyme, inositol pyrophosphates increased by 6.5-fold. This enzyme has an interesting fold and performs a non-standard phosphatase reaction; the structure was published in collaboration with Stephen Shears (Wang et al., 2018, J Biol. Chem 293, 6905-6914) and also by Tyler Florio in Gino Cingolani's group (Florio et al., 2019, Biochemistry 58, 534-545).

We have been investigating the stress resistance phenotypes shown by the siw14 mutant to determine the underlying mechanisms. Victoria Morrissette and Elizabeth Steidle examined changes to phenotypes, inositol pyrophosphates and gene expression and focused on the increased nuclear localization of the transcription factor Msn2. The siw14 mutant is resistant to heat, oxidative and osmotic stresses. The increased localization of Msn2 can explain the increased expression of stress response genes and the stress-resistant phenotypes (Steidle, Morrissette, et al., 2020, J Biol. Chem. 295, 2043-2056).

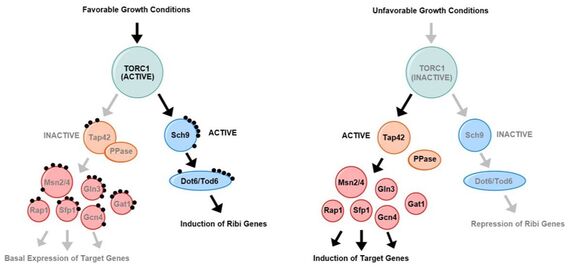

We hypothesize that altered levels of inositol pyrophosphates affect signaling through the TORC1 complex, leading to altered nuclear localization of Msn2, as shown in the figure to the right, but also to other transcription factors including Gln3, as shown below. The data supporting this hypothesis was published in the 2020 JBC paper, and was further developed in a subsequent manuscript (Morrissette and Rolfes, 2020, Current Genetics 66, 901-910) Current work is investigating the mechanisms for how altered inositol pyrophosphates might be affecting the TOR signaling pathway.

Model for role of inositol pyrophosphates.

Under favorable growth conditions (left side), TORC1 is active leading to the inhibition of a number of transcription factors (Msn2/4, Gln3, Gat1, Rap1, Sfp1 and Gcn4) and the activation of Dot6/Tod6 and induction of pro-growth genes, such as the ribosome biogenesis (RiBi) genes.

Unfavorable growth conditions are the reverse.

High levels of inositol pyrophosphates mimic the unfavorable growth conditions, possibly by direct signaling, although the mechanisms for this are under investigation.

Under favorable growth conditions (left side), TORC1 is active leading to the inhibition of a number of transcription factors (Msn2/4, Gln3, Gat1, Rap1, Sfp1 and Gcn4) and the activation of Dot6/Tod6 and induction of pro-growth genes, such as the ribosome biogenesis (RiBi) genes.

Unfavorable growth conditions are the reverse.

High levels of inositol pyrophosphates mimic the unfavorable growth conditions, possibly by direct signaling, although the mechanisms for this are under investigation.

Nutrient Metabolism: Purine Nucleotide Biosynthesis

Purine nucleotides occupy a central position in cellular metabolism. Cells maintain pools of these nucleotides to serve as the monomeric substrates for the synthesis of polynucleotides and enzymatic cofactors, to carry the high-energy phosphate bonds necessary to catalyze enzymatic reactions, and to function as second messengers within a cell.

The ability to maintain nucleotide pools is extremely important to cells. Purine auxotrophies are detected in microbes, e.g. E. coli and S. cerevisiae, that carry mutations in the biosynthetic pathway. Humans exhibit severe disorders when the enzymes essential for the uptake, interconversion and the de novo synthesis of purine nucleotides are non-functional. Deficiencies in the enzymes adenosine deaminase, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT) and adenylosuccinate lyase lead to severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome (SCIDS), Lesch-Nyhan syndrome and infantile autism, respectively.

In E. coli, regulation of expression of the purine genes occurs by a repressor protein, the PurR repressor. I cloned and characterized the gene encoding this protein as a graduate student. This protein is homologous to Lac-repressor, and is thus a member of this larger family. The mechanism for regulation by PurR is that the gene expression of the biosynthetic genes is repressed by PurR when cells are grown in medium with purines. When sufficient purines are present, the purine bases hypoxanthine or guanine interact with PurR to promote DNA binding; when the repressor is bound, RNA polymerase is unable to recognize promoter sequences and transcription is prevented.

In S. cerevisiae, regulation of expression of the biosynthetic enzymes occurs by two signaling pathways: a purine-specific pathway and a starvation pathway that

is general. Two transcription factors, Bas1 and Pho2 (a.k.a., Bas2), are necessary to activate gene expression under limiting purine conditions. The transcription factor Gcn4 induces purine gene expression under severe starvation conditions. The expression of Gcn4 is under a translational control mechanism that responds to both purine and amino acid starvation conditions, but the details of the mechanism for regulating the activity of Bas1 and Pho2 have not yet been elucidated. Current models indicate that an intermediate in the biosynthetic pathway – SAICAR – promotes an interaction between Bas1 and Pho2.

Purine nucleotides occupy a central position in cellular metabolism. Cells maintain pools of these nucleotides to serve as the monomeric substrates for the synthesis of polynucleotides and enzymatic cofactors, to carry the high-energy phosphate bonds necessary to catalyze enzymatic reactions, and to function as second messengers within a cell.

The ability to maintain nucleotide pools is extremely important to cells. Purine auxotrophies are detected in microbes, e.g. E. coli and S. cerevisiae, that carry mutations in the biosynthetic pathway. Humans exhibit severe disorders when the enzymes essential for the uptake, interconversion and the de novo synthesis of purine nucleotides are non-functional. Deficiencies in the enzymes adenosine deaminase, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT) and adenylosuccinate lyase lead to severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome (SCIDS), Lesch-Nyhan syndrome and infantile autism, respectively.

In E. coli, regulation of expression of the purine genes occurs by a repressor protein, the PurR repressor. I cloned and characterized the gene encoding this protein as a graduate student. This protein is homologous to Lac-repressor, and is thus a member of this larger family. The mechanism for regulation by PurR is that the gene expression of the biosynthetic genes is repressed by PurR when cells are grown in medium with purines. When sufficient purines are present, the purine bases hypoxanthine or guanine interact with PurR to promote DNA binding; when the repressor is bound, RNA polymerase is unable to recognize promoter sequences and transcription is prevented.

In S. cerevisiae, regulation of expression of the biosynthetic enzymes occurs by two signaling pathways: a purine-specific pathway and a starvation pathway that

is general. Two transcription factors, Bas1 and Pho2 (a.k.a., Bas2), are necessary to activate gene expression under limiting purine conditions. The transcription factor Gcn4 induces purine gene expression under severe starvation conditions. The expression of Gcn4 is under a translational control mechanism that responds to both purine and amino acid starvation conditions, but the details of the mechanism for regulating the activity of Bas1 and Pho2 have not yet been elucidated. Current models indicate that an intermediate in the biosynthetic pathway – SAICAR – promotes an interaction between Bas1 and Pho2.